งานภาพถ่ายที่พูดถึงความเชื่อมโยงระหว่างมนุษย์กับสภาพแวดล้อม หากไม่ได้เป็นในรูปแบบซาลอน (Salon Photography) หรือ พิคทอเรียล (Pictorialism Photography) ที่ส่วนใหญ่เน้นไปทางเรื่องความงามและประณีตของภาพถ่าย, งานเหล่านั้นจะแสดงถึงส่วนได้ส่วนเสียอย่างเข้มข้นเมื่อมีมนุษย์เข้าไปปรากฏตัวท่ามกลางวิถีของสภาพแวดล้อมนั้น ตัวละครทั้งหลายในภาพถ่ายถูกเชื่อมโยงเข้าไปที่มีรากฐานมาจากความจริง หรืออาจสร้างออกมาให้เหนือจริงเพื่อกลับไปสื่อสารถึงสภาวะนั้นโดยอ้อม เหมือนเป็นการแสดงตามละครที่ทำขึ้นอย่างสมบทบาทและน่าตื่นเต้น แต่หากผลกระทบต่อสภาวะธรรมชาตินั้นดำเนินอย่างต่อเนื่องไม่ได้สิ้นสุดไปตามละครฉากสุดท้ายแต่อย่างใด

เทศกาลภาพถ่ายสิบสองปันนา (Xishuangbanna Photo Festival : 西双版纳 摄影展) เป็นเทศกาลภาพถ่ายระดับนานาชาติเริ่มจัดตั้งแต่ปี 2008 และจัดอย่างต่อเนื่องทุก ๆ สองปี โดยจะเน้นเรื่องการมีส่วนร่วมของช่างภาพที่อยู่ในกลุ่มภูมิภาคลุ่มแม่น้ำโขงและนานาชาติ โดยหัวข้อหลักจะเป็นเรื่องความสัมพันธ์กันของมนุษย์กับสายน้ำอันมาจากแม่น้ำโขงเป็นสัญลักษณ์หลัก งานที่เคยจัดแสดงนั้นมีความหลากหลายทั้งสายอนุรักษ์นิยมไปจนถึงร่วมสมัย หากแต่จากการสังเกตคร่าว ๆ จากงานครั้งก่อนโดยมากจะเป็นงานแนวภาพถ่ายสารคดีตามจารีตที่มีมนุษย์เป็นตัวเดินเรื่องหลัก และมีสภาวะแวดล้อมมาประกอบ ซึ่งก็เป็นเรื่องที่ไม่เหนือการคาดเดาเท่าไรนักเพราะเป็นแนวคิดหลักของเทศกาลอยู่ก่อนแล้ว

ปีที่น่าสนใจคือปี 2018 เป็นปีสุดท้ายของเทศกาลภาพถ่ายนานาชาติขนาดใหญ่ก่อนหยุดไปจาก COVID-19 (จริง ๆ มีปีที่จัดหลังจากการแพร่ระบาดลดลงแต่เป็นขนาดเล็ก) ที่มีช่างภาพและศิลปินภาพถ่ายไทยหลาย ๆ คนเข้าร่วม เช่น มานิต ศรีวานิชภูมิ, ปิยทัต เหมทัต, มินตรา วงค์บรรใจ, กรรณ เกตุเวช ฯลฯ ที่ทำให้เห็นว่าศิลปะภาพถ่ายที่ว่าด้วยเรื่องของธรรมชาติและมนุษย์ ไม่จำเป็นต้องเป็นภาพถ่ายสารคดีหนัก ๆ เท่านั้นที่จะถ่ายทอดได้ดี แต่สามารถเป็นศิลปะภาพถ่ายที่ตีความ ‘สาระสำคัญ’ (Essence) ของเทศกาลให้กระจายไปยังกระบวนการหรือนิยามอื่น ๆ ได้ ทำให้เทศกาลที่ดูกึ่ง ๆ จะเดินตามจารีตดั้งเดิมของการถ่ายภาพเป็นส่วนใหญ่ ได้เปิดช่องแสง ฉายจับไปยังศิลปะภาพถ่ายประเภทที่ต่างออกไป

ปี 2025 เทศกาลภาพถ่ายสิบสองปันนา กลับมาแสดงอีกครั้งที่รวบรวมผลงานจากนานาชาติเหมือนปี 2018 มีผลงานจากช่างภาพและศิลปินไทยหลายคนได้รับเชิญให้ร่วมแสดงงาน, สี่ผลงานที่ถูกคัดสรรโดยผมนั้นมีข้อกำหนดกว้าง ๆ ที่ต้องเกี่ยวข้องกับมนุษย์กับสายน้ำเป็นฉากหลัง และควรสนับสนุนงานของช่างภาพรุ่นใหม่ หนึ่งในสี่งานนั้นมีงานของผมถูกส่งไปเสริมแบบไฟต์บังคับด้วย แม้อาจไม่ได้รุ่นใหม่มากนักก็ตาม

ผมพยายามพูดเรื่องการมีปฏิสัมพันธ์ของมนุษย์กับสิ่งที่แวดล้อมแบบทั่วไปที่อาจไม่ได้ตรงกับธีมงานแบบเดิมซึ่งก็ค่อนข้างใกล้เคียงกับงานของไทยที่จัดแสดงในปี 2018 ส่วนใหญ่ที่คัดไปแทบไม่มีมนุษย์ในภาพเลย เป็นการใช้ประเด็นของ ‘มนุษย์-สายน้ำ’ ทางอ้อม การใช้ผลลัพธ์หรือสิ่งที่กำลังเกิดขึ้นมาเป็นภาพแทนของการดำรงตนของมนุษย์ในฉากทัศน์ (Scenario) ต่าง ๆ ที่มนุษย์เข้าไปมีปฏิสัมพันธ์ด้วย และมีการเคลื่อนไหวของสายน้ำเป็นส่วนประกอบในฉากหลังจาก ๆ —สายน้ำเหมือนกับสัญลักษณ์ของการเปลี่ยนแปลงของเวลาที่ไหลผ่านตัวพวกเขาและพวกเราไป

งานของ สุกฤษฎิ์ ปัจจันตดุสิต (Sukrit Patjuntadusit) ที่นำเสนอภาพถ่ายชุด ‘SOMETHING IN EVERYTHING’ เป็นภาพทิวทัศน์ของริมทะเลจังหวัดระยองที่มีโรงงานอุตสาหกรรมเป็นฉากหลัง แต่หากงานนี้ไม่ได้เพียงนำเสนอภาพถ่ายแบบปกติของทิวทัศน์โรงงานที่ทำตัวเป็นอสุรกาย และน้ำทะเลรับบทเหยื่อจากสารพิษที่น่าสงสารเท่านั้น หากแต่กระบวนการสร้างงานนั้นมีการนำเอาข้อเท็จจริงเข้ามาเป็นเนื้องานของภาพถ่ายด้วย ที่ไม่ได้ประกอบเป็นวัตถุเสริมงานภาพทีหลังเหมือนตามนิทรรศการภาพถ่ายต่าง ๆ

สุกฤษฎิ์นำน้ำเสียที่ได้มาจากโรงงานมาเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของการสร้างภาพถ่ายโดยการจุ่มฟิล์มที่ถ่ายภาพทิวทัศน์โรงงานในน้ำเสียพวกนั้นพร้อมกับกระบวนการสร้างภาพถ่าย (Film Soup) จนภาพที่ออกมาบิดเบี่ยว และขาดหายไป ราวกับฟิล์มภาพถ่ายโดนน้ำเสียกัดกร่อนทำลายจนน่าสยดสยอง ซึ่งอันที่จริงเกิดจากความผิดพลาดในกระบวนการสร้างภาพถ่ายที่อาจไม่ได้เกี่ยวข้องกับน้ำที่เอามาซะทีเดียว (แต่ก็น่ากลัวอยู่ดี) อันเป็นข้อผิดพลาดแบบที่มาได้จังหวะกับแนวคิดหลักของโครงการ ทำให้งานชิ้นนี้กระโดดออกมาจากโครงสร้างเดิมของการสร้างงานภาพถ่ายแนวสารคดีที่พบเห็นทั่วไป

‘Parallel World’ ของ สาธิตา ธาราทิศ (Satita Taratis) งานอีกชิ้นที่เกี่ยวข้องกับเรื่องสิ่งแวดล้อมเป็นงานอันดูเรียบง่ายแต่แฝงด้วยความหมายลึกซึ้งของการคาบเกี่ยวกันของพื้นที่ และสถานการณ์สิ่งแวดล้อมที่ต่างกันแบบสุดขั้วในแต่ละภาพ ตัวงานนำเสนอภาพแนวกว้างขนาดเดียวกับจอภาพยนตร์แบบ Ultra Panavision 70 (2.76:1) การจัดเรียงวางรูปแบบนิทรรศการจะวางเป็นแนวยาวให้เกิดการเชื่อมต่อกันในแนวคิดของโลกใบเดียวกัน แต่ต่างกันอย่างสิ้นเชิงในสภาวะคล้ายกับ ‘แถบค่าแสงเสปกตรัม (Spectrum Band)’ ที่ต่อเนื่องกันไปจนค่อย ๆ ต่างกันในที่สุด, ไหลวน-ถ่ายเทกันไปมาในพื้นที่อันซับซ้อนของระบบนิเวศ

งานชิ้นนี้ของสาธิตาเคยจัดแสดงในนิทรรศการกลุ่ม ‘นักตีความ’ ที่ MOCA ปี 2022 แต่ด้วยข้อจำกัดของพื้นที่ที่ต้องจัดสรรทำให้แนวคิดการจัดวางแบบ Spectrum Band นี้ไม่ได้ทำในตอนนั้น เมื่อได้พื้นที่พอสมควร จึงจัดวางงานชุด Parallel World ให้เป็นอย่างที่ควรจะเป็น (ตอนเขียนนี้ยังไม่ได้เห็นว่าตรงตามที่ออกแบบไปหรือไม่ ถ้าได้เห็นแล้วจะนำมาให้ดูอีกที)

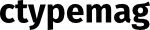

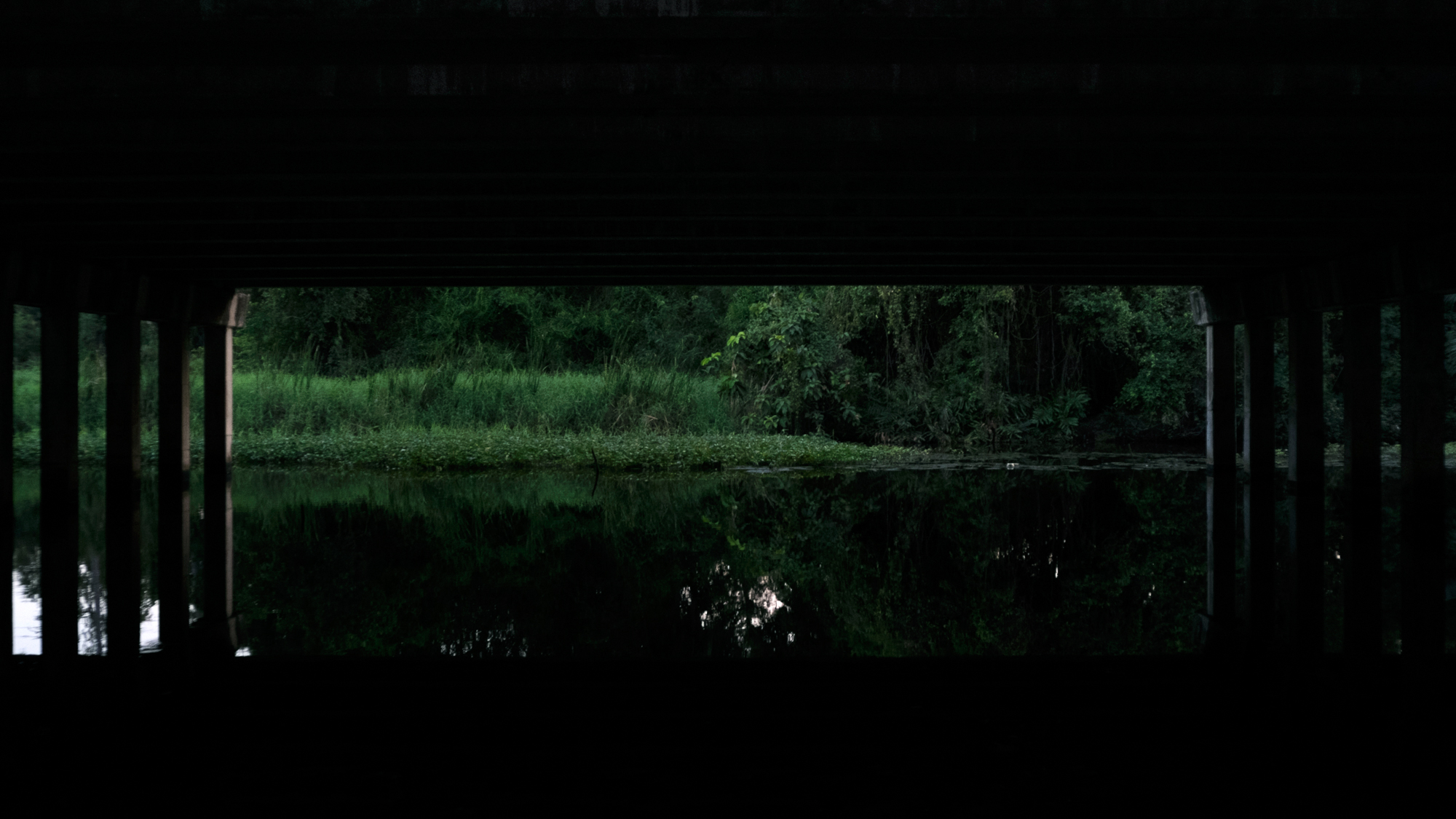

งานชิ้นถัดมาคืองานของผมเองที่ทำงานไว้นานแล้ว (2019) ตั้งแต่ย้ายบ้านมาที่รอบนอกของกรุงเทพฯ ริมทางด่วนขนาดใหญ่ที่มีเหมือนคลองส่งน้ำอยู่ข้างใต้ เป็นงานชุดที่มีชื่อว่า ‘โรงมหรสพ’ (Theatres) แสดงภาพของช่องระหว่างต้นเสาทางด่วนที่สามารถมองทะลุจากฝั่งถนนไปยังสิ่งที่อยู่ตรงข้ามได้ ภาพที่ปรากฏนั้นมีทั้งพืชพันธุ์รกครึ้ม บ้านเรือนที่อยู่อาศัย ความเจริญและความเสื่อมโทรม เป็นภาพจำลองการนั่งมองจอภาพยนตร์ที่ฉายเรื่องราวต่าง ๆ ก่อนที่จะมีทางด่วนเกิดขึ้น เป็นการมองด้วยสายตาที่เป็นกลางอย่างแนวคิดของขบวนการศิลปะภาพถ่าย ‘New Topograhics’ ในช่วงยุค 70s ตัวงานจะไม่ตัดสินว่าสิ่งนั้น ๆ ดีหรือไม่ดี หน้าที่ของมันคือการแสดงให้เห็นว่ามีอะไรในภาพนั้น ส่วนการคิดต่อ (หรืออาจจะไม่คิด) คือหน้าที่ของผู้ชมงาน แต่เอาเข้าจริงแนวคิดพื้นฐานมักถูกโน้มน้าวบาง ๆ จากศิลปินอยู่ในทีอย่างปฎิเสธไม่ได้

งานชิ้นสุดท้ายที่นำไปแสดงคืองานของช่างภาพสตรีทที่ชื่อ อัษฎางค์ สัตสดี (Audsadang Satsadee)ในชื่อชุดงาน ‘Living on the Cloud’ ด้วยงานของอัษฎางค์ เป็นงานที่เกี่ยวข้องกับมนุษย์อย่างตรงไปตรงมาต่างจากอีกสามงานที่พูดถึงก่อนหน้านี้ จึงค่อนข้างท้าทายว่าการนำภาพชุดแนวสตรีท (Street Photography) มาแสดงจะเข้ากับรูปแบบของเทศกาลภาพถ่ายนี้หรือไม่

งานของอัษฎางค์ชุดหลัง ๆ ไม่ได้โน้มเอียงไปทางภาพสตรีทสมัยใหม่นัก และมีเนื้อหาที่สัมผัสได้ถึงรูปแบบหนึ่งอย่างเด่นชัด คือการที่หน้าเลนส์หันไปหาผู้คนในชนชั้นแรงงานระดับกลางถึงระดับล่าง และเนื้อหาของภาพ (แม้จะโดยตั้งใจหรือไม่ตั้งใจก็ตาม) สามารถสื่อสารถึงเรื่องราวส่วนเล็ก ๆ ส่วนหนึ่งของเหล่าผู้คนที่มีความสำคัญต่อการพัฒนาเมืองได้อย่างน่าสนใจ โดยงานชุดนี้นำเสนอเรื่องการพักผ่อนหย่อนใจในกิจกรรมและสถานที่ต่าง ๆ ทำให้นึกไปถึงงานภาพถ่ายอีกหลายงานที่พูดถึงชนชั้นแรงงานที่ใช้ชีวิตยามว่างตามสถานที่ต่าง ๆ กันอย่างหนาแน่น เช่น ชายหาด สวนสาธารณะ สวนสัตว์ ริมแม่น้ำ ฯลฯ เป็นการหยุดพักผ่อนบนชั้นเมฆที่อ่อนนุ่มบางเบา, หากไม่นานก็ต้องกลับลงมาทำงานต่อบนพื้นดินอันแข็งกระด้างของความจริงอีกครั้ง—วนลูปต่อเนื่องกันไปเหมือนติดกับดักที่มองไม่เห็น

งานทั้งหมดจะถูกจัดแสดงที่จังหวัดสิบสองปันนา มณฑลยูนนาน ประเทศจีน ตั้งแต่เดือนตุลาคมจนถึงธันวาคม 2025 ครั้งนี้เดินทางไปร่วมงานด้วยครั้งแรก (เสียดายไม่ได้พาศิลปินไปด้วยเนื่องจากข้อจำกัดต่าง ๆ ของทางเทศกาล) และหวังว่าจะได้คัดสรรงานของคนไทยไปอีกในอีกสองปีข้างหน้าถ้าเป็นไปได้ ขอบคุณพี่โอ๋ปิยทัตที่ให้โอกาสในการคัดสรรงานครั้งนี้

Photography that addresses the connection between human beings and the environment, if not expressed through Salon Photography or Pictorialism Photography, forms that often emphasize beauty and refinement, tends to reveal much sharper tensions when people appear within the rhythms of nature. Figures in such photographs are tied to narratives grounded in reality, or constructed in a way that bends toward the surreal, in order to indirectly reflect those conditions. It is almost like a theatrical performance: well-acted and compelling, yet unlike theater, the impact on nature does not end with the closing scene.

The Xishuangbanna Photo Festival (西双版纳摄影展), first established in 2008, is an international photography festival held every two years. Its focus lies on the participation of photographers from the Mekong region as well as from around the world. The central theme revolves around human relationships with water, with the Mekong River as its symbolic axis. Works presented at the festival have ranged widely from conservative to contemporary practices. Yet, based on past editions, the dominant tendency leaned toward conventional documentary photography, where humans are the central actors and the environment provides the backdrop. This, of course, aligns with the core concept of the festival.

The year 2018 marked an especially significant edition, it was the last major international festival before being halted by COVID-19 (later editions were much smaller). That year, many Thai photographers and photographic artists participated, including Manit Sriwanichpoom, Piyatat Hemmatat, Mintra Wongbanchai, and Gun Ketwech, etc. Their presence revealed that photography exploring the relationship between nature and humanity need not be confined to traditional documentary form. Instead, it can extend to interpretations that communicate the “essence” of the festival through alternative processes and definitions. In doing so, the festival, often perceived as rooted in tradition, opened a channel of light onto other forms of photography.

In 2025, the Xishuangbanna Photo Festival returns once again as an international gathering, recalling the scope of the 2018 edition. Several Thai photographers and artists were invited to take part. From the four works I selected for this edition, the only broad criteria were that they relate to human beings and water as the backdrop, and that they help support the work of younger photographers. One of the four happens to be my own work, added almost by necessity, even though I may not exactly qualify as “emerging.”

My attempt was to discuss human-environment interaction in a more indirect sense, departing somewhat from the festival’s traditional thematic approach. Much like many of the Thai works shown in 2018, the photographs I chose contain almost no people at all. Instead, they approach the theme of “human–water” obliquely, using consequences or traces of human presence as proxies for lived scenarios of interaction. Flowing water, faintly visible in the background, becomes a symbol of time itself, passing over them and us alike.

Sukrit Patjuntadusit’s series SOMETHING IN EVERYTHING presents seascapes from Rayong province, with industrial factories looming in the background. Yet this is not merely a straightforward depiction of monstrous factories against a poisoned sea. Instead, Sukrit incorporates factual material directly into the photographic process. The work does not rely on supplementary documentation displayed alongside the images, as is often seen in exhibitions. Rather, wastewater collected from the factories themselves was used in the process of developing the photographs: he soaked exposed film in this polluted water during the film-soup stage. The results are images distorted, scarred, and dissolved, appearing as though the film had been corroded by toxic waste. While in fact the destruction stemmed from technical accidents not entirely related to the water, the unsettling effect aligned seamlessly with the project’s concept. This accident transformed the work into something that breaks away from the structures of conventional documentary photography.

Another work, Parallel World by Satita Taratis, engages with environmental issues in a subtle yet profound way. Each wide-format photograph is presented in the cinematic proportions of Ultra Panavision 70 (2.76:1). The exhibition layout arranges the images in a long horizontal band, creating continuity under the idea of “a single world” that nonetheless contains drastically opposing environmental conditions. The sequence resembles a “spectrum band,” shifting gradually yet inevitably, reflecting the fluid exchange across the complexities of ecosystems. Satita previously exhibited Parallel World in the group show The Interpreters at MOCA in 2022, though space limitations then prevented the full realization of the spectrum-band arrangement. With a larger exhibition space now available, the work can finally be installed as intended (though at the time of writing, I have not yet seen the final result).

My own contribution is an older series titled Theatres (2019), created after I moved to the outskirts of Bangkok near a major expressway. Beneath its towering pillars runs what resembles a canal. The series captures views through the gaps between the expressway columns, openings that frame scenes of dense vegetation, houses, signs of development, and decay. These photographs resemble cinematic screens, projecting the landscapes that existed before the expressway appeared. The perspective is neutral, reminiscent of the New Topographics movement of the 1970s, which refrained from moral judgment and focused on showing “what is there.” Of course, the artist’s perspective subtly shapes the framing, whether or not it admits bias.

The last selected work is Living on the Cloud by street photographer Audsadang Satsadee. Unlike the previous three, Audsadang’s work engages with humanity directly, raising the challenge of how street photography might fit within the festival’s broader framework. His recent series does not lean toward new street photography style, but instead shows a consistent focus: turning his lens toward working- and lower-middle-class communities. Whether intentional or not, his images reveal small but meaningful fragments of lives that are central to urban development. Living on the Cloud portrays moments of leisure, people resting, enjoying public spaces, beaches, zoos, riverbanks. These photographs recall traditions of documenting laboring classes during their rare downtime. The “cloud” here suggests a soft, fleeting respite, before inevitably descending again to the hard ground of daily labor—a cycle that repeats endlessly, like an invisible trap.

All these works will be exhibited in Xishuangbanna, Yunnan Province, China, from October through December 2025. This will be my first time attending in person (unfortunately, I could not bring the artists themselves due to the festival’s constraints). I hope to continue selecting and presenting Thai works again in the next edition, two years from now. My thanks go to Piyatat Hemmatat for giving me the opportunity to curate for this festival.